How Chris Jackson Is Building a Black Literary Movement

On an unnervingly balmy November day, the scene at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn was restless and expectant. Ta-Nehisi Coates was scheduled to appear on campus for a discussion about his best-selling book, ‘‘Between the World and Me.’’ Evers has a student body that is over 80 percent black, and interest in the event was palpable. Outside, on Bedford Avenue, a diasporic survey of music — reggae, soca, R.&B., trap — flew out the windows of rusted sedans as a slow parade of students filed into the building: a group of young men in near-identical oxfords and knit ties; a woman in a knee-length camouflage hoodie, black tights and Timberland boots; kids wearing mohawks, flattops, cornrows and uncountable Afros.

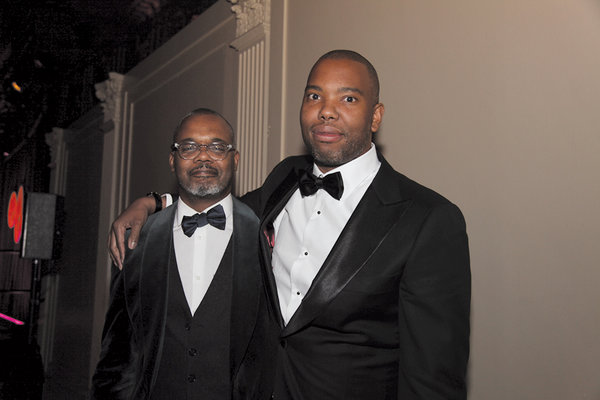

Coates was running late, and the director of the school’s Center for Black Literature, a stocky man with yellow-brown skin, closely cropped hair and a heather gray goatee, was worried about the time. He turned to the man standing next to him: Chris Jackson, Coates’s book editor. ‘‘When do you think he’ll get here?’’ he asked. ‘‘We set up a greenroom for him to relax and have some water before the talk, but we’ve only got so much time.’’

‘‘He’s . . . ’’ Jackson said, trailing off. ‘‘He’s on his way. He had a thing right before this, and he’s got a thing right after. It’s crazy these days.’’

That was perhaps an understatement. That year, Coates won a MacArthur ‘‘genius’’ grant, was tapped to write a new installment of Marvel’s ‘‘Black Panther’’ comic series and saw ‘‘Between the World and Me’’ nominated for the National Book Award. Coates’s book — and his ongoing tour of the country to promote it — was the latest peak in Jackson’s career. Over the last decade and a half, Jackson has ushered into being the works of category-defying novelists like Victor LaValle and Mat Johnson, polemicist-experientialists like Coates and the civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson and pop-cultural vanguardists like the chef-memoirist Eddie Huang and the rapper-entrepreneur Jay Z. To the extent that 21st-century literary audiences have been introduced to the realities and absurdities born of the phenomenon of race in America, Jackson has done a disproportionate amount of that introducing.

That day in Brooklyn, Jackson wore glasses, a plaid shirt open to just below the clavicles and shoes with insouciant laces that looked ready to untie themselves at any moment. The descriptive cliché about tall people is that they tend to bend over at the waist or, worse, at some hump-inducing point along the spine — presumably in order to make others feel more comfortable. But Jackson’s bearing was unapologetically erect, even as he kept glancing down at his phone, looking for word from his author. While we waited, he told me about a recent trip to the Texas Book Festival, where he accepted the Kirkus Prize on Coates’s behalf.

‘‘The whole time,’’ he said, ‘‘I was just waiting for, you know, it to happen. And, sure enough, a very sweet-looking white woman walks up to me, very politely, and says, ‘Mr. Coates?’ Which is a thing that has happened to me more times than I can count. I’ve been mistaken for Colson Whitehead — who has long dreads — Dinaw Mengestu, Ta-Nehisi a few times, you name it. Sometimes by colleagues I see every day in the elevator, or even people who claim to know the writer in question. Anyway, I guess the woman was embarrassed, and so, of course, was I, but she still went ahead with what she’d been planning to do with Ta-Nehisi: unload all this terrible racial guilt. What am I supposed to do with that? Ta-Nehisi hears that stuff all the time. It’s just — ’’ He paused for a moment. ‘‘It’s exhausting.’’

Coates arrived and greeted Jackson with a hand on the shoulder before he was whisked upstairs to the cafeteria, where by now hundreds of students, faculty members and administrators sat waiting for the talk to begin. Jackson was seated close to one side of the podium, but at some point he slipped out of his seat and materialized toward the back of the room. He stood there throughout the event, arms crossed loosely over his chest, half hidden by a wall of black draping, watching his author with a mix of protectiveness and amusement.

A photograph of Jackson taken in 2010 at Coachella works as a tidy metaphor for his singular role as an editor. Jackson had accompanied Jay Z and Beyoncé to the music festival in search of material for what would become ‘‘Decoded,’’ a book-length exegesis of Jay Z’s lyrics, written by Jay Z himself. The image captures the three of them — Jackson just off to the side — standing in front of a mesh fence. Behind them are countless palm trees, sprouting open into an opaque sky. Everything else is chaos: Onlookers, some shirtless, form a horseshoe around the trio, smartphones and cameras aloft. The picture is a kind of grotesque, conveying something nameless and sick about the nature of American celebrity, and how it sometimes mirrors the ever-unfolding, sideshow drama of race; Jackson, Jay Z and Beyoncé seem to be the only black people in frame.

‘‘Decoded’’ had a real, if comically belated, impact on how the wider world approaches the content of lyrics in rap. Just two years after its release, for instance, the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz invested $15 million in a start-up, Rap Genius, that encourages the same sort of close reading. Jackson’s role, then, is to perform nothing less than a kind of magic. He stands between the largely white culture-making machinery and artists writing from the margins of society, as well as between the work of those writers and the largely white critical apparatus that dictates their success, in both cases saying: This, believe it or not, is something you need to hear.

The book that perhaps best encapsulates that ethos is one of Jackson’s first, ‘‘Step Into a World: A Global Anthology of the New Black Literature,’’ published in 2000. The collection, which he and the ‘‘Real World’’ star turned hip-hop journalist Kevin Powell compiled, brought together a cohort of writers — Junot Díaz, Edwidge Danticat, Paul Beatty, Hilton Als, Claudia Rankine and others — who have today come to form a loosely generational, unabashedly multicultural alternate literary establishment. ‘‘Step Into a World’’ marked a turning point for Jackson, who had until then been publishing reference works that were the stock in trade of John Wiley & Sons, where he worked at the time.

‘‘I’ll never forget a reading we did for that book,’’ he told me. ‘‘It was at the Schomburg’’ — the Harlem library that is a repository of black literature and history — ‘‘and there were so many people there, not just publishing people, as we usually think of them, but people from the neighborhood, and they were picking up this book.’’ He paused here, after uttering the word book, and his abiding wonder at the power of the object was almost tangible. ‘‘This book, containing all these ideas that were so important to me. They were picking it up and leaving with it, and it was such a wonderful literalization of the transmission of ideas.’’

Compilations like ‘‘Step Into a World’’ have tended to play an outsize role in the history of black artistic and intellectual achievement — maybe because of their emphasis on collectivity, on ‘‘movements,’’ a canny response to the difficulty of individual advancement in the literary arena. The most prominent example of the genre is perhaps ‘‘The New Negro,’’ published in 1925, which heralded the arrival of the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by the Howard University philosophy professor Alain Locke and dedicated, rather grandly, to ‘‘the Younger Generation,’’ the volume included contributions from Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Hurston, Arna Bontemps and Langston Hughes. It also contained a short treatise on black comedy in the theater by Jessie Fauset, who served for eight years as literary editor of the N.A.A.C.P.’s magazine, The Crisis, and whom Hughes credited as one of the people who ‘‘midwifed’’ the movement. Fauset corresponded widely with Renaissance figures, and her letters reveal a deft, coaxing way with writers. She folds criticism seamlessly into flattery, identifying the writer’s most consequential gift and encouraging its cultivation. Jackson fills a similarly multifaceted role today — gatekeeper, encourager, cool-but-kind appraiser of talent — and might be the first 21st-century example of a 20th-century type: the black editor as not only acquirer, tweaker and disseminator but also as movement-shaper.

There is, upon inspection, a kind of coherence among the books that Jackson has taken on over the course of his career, especially recently, as executive editor at Spiegel & Grau, a post he has held since 2006. Each of his most famous books is a kind of jeremiad: Bryan Stevenson’s 2014 ‘‘Just Mercy,’’ for example, flits between an honest accounting of America’s racial past and present and an electric, almost Whitmanian optimism about the future. Matt Taibbi, best known for his scathing commentary and reportage in Rolling Stone, reaches Pentecostal levels of urgency in ‘‘The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap,’’ also published in 2014. Jill Leovy’s hit last year, ‘‘Ghettoside,’’ reveals one of the many undersides of American life — the startling frequency of black male death — with a quiet, morbid awe.

The contemporary success of this kind of polemic feels perfectly natural: There is, after all, something simultaneously argumentative and explanatory, and therefore inherently essayistic, about the rhetoric of today’s activist culture. The prose to which Jackson seems drawn links the sermon — the original American form of address, starting with John Winthrop’s ‘‘City Upon a Hill’’ — to the publishing industry’s current appetite for narrative nonfiction. Bringing this synthesis to popular acclaim is Jackson’s great and continuing achievement. The mix of registers and voices and styles on display in ‘‘Step Into a World’’ hints at the potential power of this fusion. The inclusion of a cadre of hip-hop journalists, many of them from Vibe magazine, was particularly prescient. ‘‘For me,’’ Jackson says, ‘‘Vibe was the magazine of American culture. Not just hip-hop culture, not just black culture, but American culture.’’

This insistence on the full and distinctive Americanness of the Vibe generation influenced the advice Jackson gave to the first raft of writers whom he published at Crown, where he landed in 2000 after the success of ‘‘Step into a World.’’ ‘‘I just told them to bring me their biggest ideas,’’ he says, ‘‘and not to think about what would make a great black book or whatever. The lens that we have is a way in which we can claim the entire world.’’

Jackson’s life before entering the literary arena prepared him well to articulate the polarity of American experience. He grew up in Harlem during the 1970s and ’80s, first in the city housing authority’s Grant Houses, at 125th Street, then in the monolithic Lionel Hampton Houses, then in a tenement nearby. There, Jackson says, ‘‘our downstairs neighbor was murdered, a shooting happened right around the corner while my sister was coming home from school and another neighbor turned his apartment into a crack den.’’

Jackson treats this subject matter-of-factly, with a hint of tragicomedy and an eye sensitive to unlikely beauty: ‘‘Our next-door neighbors were these two boys who became big dealers — they were beautiful boys, S-curls and gold ropes and new Jeep Cherokees parked outside, and always polite,’’ he says. ‘‘And they terrified me.’’

His father died when Jackson was 4, leaving his mother, an observant Jehovah’s Witness, to raise him and his two siblings. Jackson left the church when he was a student at the prestigious Hunter College High School, on the Upper East Side, but returned at the urging of his mother while she battled cancer. She died when he was 18, and when he left the church again in his 20s, it was for good. His official renunciation of the religion meant he was cut off from his siblings.

Jackson had already fallen under the spell of publishing during his high-school days, working for a book packager, James Charlton Associates, as part of an internship. He worked at another publishing house before enrolling at Columbia University. Soon, he found his way to John Wiley & Sons. He took part in the quickly intermingling hip-hop and literary scenes of the ’90s, frequenting places like the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and writing his own essays and reviews.

Jackson says that when he looks back at that time, he sees a ‘‘depressed orphan who lost his family to a crazy religion and consoled himself almost exclusively with books.’’ This loneliness was compounded by his feeling that he wasn’t a true native of either of the worlds he inhabited. ‘‘I’d spent my educational and work life from the time I was 7 in predominantly white, semi-elitist institutions,’’ he says. ‘‘The full package made me a little weird.’’ That package also helped him refine an approach to his job that the hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons, with whom he worked briefly on a book project, helped him articulate. ‘‘He would always talk about there being two kinds of record executives: inside-the-building guys and outside-the-building guys,’’ Jackson says. ‘‘The inside guy is the one who sits in his office all day, waiting for the talent to land in his lap. The outside guy is the one who’s in the clubs every night, looking for the next big thing, even if they’re not as polished.’’

Jackson has had to be both. The facts of his life in publishing speak to his inevitable place on the inside: the glass-enclosed office; the bookstore — McNally-Jackson in SoHo, which he helped open with Sarah McNally, who was then his wife — that has now become a New York literary institution; his naming last year as a Publishers Weekly Notable of the Year. Still, he has also acted as a one-man A.&R. unit: He spends much more time corresponding with emerging writers than with the agents who are prone to sending him their most generic ‘‘black’’ offerings.

‘‘Chris is very independent,’’ says Rachel Klayman, vice president and executive editor at Crown Publishers. Klayman worked with Jackson at Crown in the early 2000s, and has remained one of his closest friends in publishing since then. ‘‘At this point,’’ she said, ‘‘he’s sort of an autonomous region. His list is so distinctive.’’ To Klayman, who remembers the time — not too distant — when the conventional wisdom was that ‘‘black books don’t sell,’’ Jackson’s intellect and curatorial instincts have made room for new, original voices. ‘‘He’s just been so steadfast and consistent in pursuing these books,’’ she said. ‘‘Over time, he has proven that there is a market for them. A very substantial market.’’

Despite his success, he still senses a certain condescension within the industry. ‘‘I’m sensitive to that,’’ he says, ‘‘people treating me like I’m here by their grace in some way, that they are welcoming me to something that I helped build.’’ Here, if you need it illustrated, is how good intentions so often miss their mark; how an industry that prides itself on its progressive politics can almost wordlessly become an alienating place for a person like Jackson.

It’s a feeling he has had since his high school days on the Upper East Side: ‘‘The only way to get into Hunter is to pass the test,’’ he says. ‘‘There’s no affirmative action; you just gotta pass the test. And almost nobody passes the test. So if I’m there, it’s because I passed the test. I’m not there because somebody did me a favor. So don’t look at me like I don’t belong here. Which is what happens. So I think from an early age, I developed this aversion to that attitude that I have dealt with, in part, by looking for support outside of the industry. Which is why — white, black, whatever — I love talking to writers, because we’re talking about the thing that they care about, which is writing, and their ideas.’’ In other words: as equals.

One afternoon in November, after the talk at Medgar Evers, I met Jackson at a French bistro across the street from his office. The place was dimly lit, and there were minutely drawn maps and fake frescoes on the walls. Our conversation started with the idea of responsibility. More precisely: I spoke of responsibility, and he humored me. I was worried, I shared, as an accordion-led melody played around us, about falling short of some standard in my writing, including the article I was writing about him. It wasn’t quite enough for my work to be published, or well received, or even satisfying to me on the level of aesthetics. I perceived my efforts, such as they were and are, as part of a long and significant and exacting tradition, and there was something — I couldn’t quite name it — that I owed. I felt bound inextricably to . . . to something. While I talked, Chris nodded.

‘‘What is the tradition that we’re even talking about?’’ he asked, not completely rhetorically. ‘‘I certainly feel responsibility to something, too.’’ He stopped for a moment, looked downward, then back at me.

‘‘The great tradition of black art, generally,’’ he started again, ‘‘is the ability — unlike American art in general — to tell the truth. Because it was formed around the great American poison, the thing that poisoned American consciousness and behavior: racism. And black culture, such as it is, was formed around a necessary resistance to this fundamental lie. That’s the obligation. And this is the power that black art has.’’

This power — the power of the unvarnished truth — is what is at stake when we talk about the problem of exclusion in the world of books. What believable version of American reality can be the product of an industry that, according to a recent survey, counts black people as just 4 percent of its employees? We can admit that race is not our only national reality without denying that it clarifies the workings of — and relations among — the others. A kind of American Rosetta Stone.

This is the unique claim on the truth that black art can make: It draws its energy from its embrace of hybridity, from a rejection of the illusion of American purity. The joy of expression and the sorrow of experience, properly commingled, might result in something new — and true.

Jackson — yes, privileged by his rarefied position in publishing, but also still attuned, by dint of birth and background and experience, to the distorting effects of race — finds himself at the straining center of these extremities.

‘‘I want to protect the writer, of any race, from the dishonesty of racism, and how it can inflect any kind of work,’’ he said. ‘‘And, for writers who are trying to challenge the pandering of the white gaze, if you have to go through a series of gatekeepers who are uniformly white, you’re going to end up with something that’s’’ — here came a considered pause — ‘‘it’s going to be tough to preserve the integrity in the end.’’

In January, I called Ta-Nehisi Coates at his home in Paris. Finally done with his book tour, he had retreated to Europe and was preparing for the release of a French translation of ‘‘Between the World and Me.’’ He told me about the beginning of his relationship with Jackson. The two first crossed paths when Coates was working at The Village Voice and shopping around ‘‘a really bad pitch’’ about the history of hip-hop. After that proposal was ‘‘thankfully rejected,’’ they stayed in touch, searching for the kernel of a book. At a cafe one day, Coates offered more ideas. ‘‘But then,’’ Coates said, ‘‘I started talking about my dad, and he said, ‘Well, that might be a book.’ ’’

The editor was right: Coates’ reflections on his father eventually became ‘‘The Beautiful Struggle,’’ Coates’s lyrical debut memoir. In the intervening years, Jackson’s eye has become indispensable to Coates, largely because of the depth of their shared experiences. ‘‘You can’t say to Chris, ‘You don’t really know about the struggle,’ ’’ Coates said. ‘‘Chris knows. And if Chris doesn’t get it, you need to go back to Square 1. That’s rare for black authors. Very, very rare.’’

The history of the Greek Revivalist behemoth at 55 Wall Street, now home to Cipriani, is a history of Manhattan itself. Here float the ghosts of robber barons, real estate titans, politicians, thieves. The National Book Awards were held here in November, and the permanent features of the place — great marbled columns, chandeliers, arcades, a gaudily patterned dome — dwarfed the temporary signs of the awards ceremony: an elevated stage, draped in velvet, decked on both sides by stairs, sat along one of the walls. Near another wall was an afterthought of a red carpet.

Before the ceremony began, cheesy horn-led jazz played while the faces of the nominees, their books beside them, flashed across screens. Journalists fidgeted with laptops. Wineglasses in the hundreds twinkled periodically under the light. Upstairs, on a shallow mezzanine, there was a makeshift cocktail reception, packed wall to wall, and while wading through the crowd, I was grabbed by a short man with a shaggy haircut and a white beard.

‘‘Hey,’’ he said, squinting. ‘‘Ta-Nehisi?’’

I wasn’t dressed like a nominee for a literary award, with my tweed blazer, infelicitous beard and shabby steno pad. ‘‘No,’’ I said. ‘‘Not the guy.’’

Then came a rapid series of tortured gestures: a wince; a vague and useless raising of the hands. ‘‘Sorry,’’ he said. Then, to a friend: ‘‘He really does look a lot like Ta-Nehisi.’’ (Which, well, I don’t, not close.) I smiled and walked away.

Back downstairs, in a corner of the fast-filling room, Jackson stood waiting, a long bronze medallion — an adornment for each nominee — slung over one forearm. ‘‘Ta-Nehisi just needs to take some pictures with this medallion, do an interview on the red carpet before the ceremony starts.’’

Coates arrived, tuxedo-clad, with his wife, grabbed the medallion, took the photos. Nonfiction was the second-to-last award of the night, and when Coates won, to prolonged applause, he gave a speech that was a kind of recitation of his book’s searing theme, and that made noticeable use of the first-person plural. Speaking of the book’s refusal to accept or ignore the ‘‘lie’’ of American racism, he turned toward Jackson and said: ‘‘That was what we did with ‘Between the World and Me.’ That was what we did, Chris.’’

After the ceremony, the poet Terrance Hayes came loping up to the front of the room, where Jackson was receiving a steady stream of congratulators. ‘‘Chris, man, how’s it feel to be you?’’ Hayes asked, smiling. ‘‘You’re like P. Diddy out here, making all these geniuses. Like Phil Jackson or somebody like that.’’

Jackson just grinned and shook his head, kept grabbing hands.

Later though, over email, on several occasions, I asked him the same question: How does it feel?

The litany helped clarify the stakes for Jackson’s work. It is undeniable that the rise of the so-called meritocratic elite has cleared the way for certain exceptional members of recently oppressed minorities to operate, and sometimes even succeed, at the highest levels of American society. What it has so far failed to deliver — what it was never, perhaps, quite engineered to ensure — is a full sense of arrival. Of belonging. And in this country whose heart has always been moved, perhaps inordinately so, by a phrase nicely turned, it might just be that art — argumentative, confrontational art; art obsessed with a fair hearing of the truth — is the vessel through which this hope might be realized.

‘‘Maybe it fuels your desire to not just do good work,’’ he wrote, ‘‘but to beat them in a way that changes the game, that uproots some of that stupidity and blindness.’’ He continued, ‘‘When you asked about what unites this generation of black writing, I think there’s something of that to it — not just to be accepted or included or even to define our work in opposition to the mainstream, but to go our own way with some kind of integrity, rigor and honesty.’’

‘‘And,’’ he wrote, ‘‘to win.’’

Correction: February 14, 2016

An article on Feb. 7 about the editor Chris Jackson referred incorrectly to his college education. He attended Columbia University but did not graduate.

via How Chris Jackson Is Building a Black Literary Movement